There are many good reasons to use the KJV (the King James Version of the Bible), its accuracy compared to most other Bible versions being the main one, and if non-TR (Textus Receptus) manuscripts truly are corrupt (or even if they’re just less accurate than the TR), as many Christians who fall under the label of KJV-Onlyist believe, that would be another good reason for them to prefer it over other non-TR-based Bible translations. Many of these particular Christians have another reason they only use the KJV, however, and that’s because they believe God promised to preserve His words in written form in Psalm 12:6-7, and they then assume the KJV is that set of preserved words in written form.

Now, this is technically two claims (that God promised to preserve His words in written form for ever — although it’s also important to remember that “for ever” rarely, if ever, literally means “without end” in the Bible, as demonstrated from Scripture here — and also that this promise was fulfilled through the KJV), but we’re only going to look at the first claim in this particular article. And while there are various other passages they refer to as well, in order to try to defend this assertion (although, if you look at them in context, you’ll see that many of those other passages are actually referring strictly to prophetic words that had just been spoken immediately beforehand, or else to other specific words within Scripture such as the Mosaic law rather than to Scripture as a whole, particularly in written form), as I already mentioned, they primarily use Psalm 12:6-7 to back this claim, because it says:

The words of the Lord are pure words: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt keep them, O Lord, thou shalt preserve them from this generation for ever.

Of course, if you only read those two verses on their own, cherry-picking them out from among the rest of the chapter they’re a part of, it’s easy to see why someone might assume they’re talking about preserving Scripture in written form. Is that actually what those two verses are referring to, though? As the old saying goes, a text read out of context is just a pretext for a “proof text,” so we have to look at the context of the psalm as a whole in order to determine what those two verses near the end of it are really talking about rather than just using them as a “proof text” on their own to prove a specific doctrine. Of course, what most people don’t really notice when reading the psalm is that it consists of three separate parts, so let’s see how the chapter looks when that fact is taken into consideration, in order to discover context of the whole psalm:

Part 1 (verses 1-2), the words of the Psalmist: Help, Lord; for the godly man ceaseth; for the faithful fail from among the children of men. They speak vanity every one with his neighbour: with flattering lips and with a double heart do they speak.

Part 2 (verses 3-5), the words of the Lord: The Lord shall cut off all flattering lips, and the tongue that speaketh proud things: Who have said, With our tongue will we prevail; our lips are our own: who is lord over us? For the oppression of the poor, for the sighing of the needy, now will I arise, saith the Lord; I will set him in safety from him that puffeth at him.

Part 3 (verses 6-8), the words of the Psalmist: The words of the Lord are pure words: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt keep them, O Lord, thou shalt preserve them from this generation for ever. The wicked walk on every side, when the vilest men are exalted.

When you break the psalm down into its three respective parts, we can see that it’s talking about three different groups: the wicked, the needy, and God, with:

1) The psalm beginning as a cry for help to God by the psalmist because of wicked men oppressing the needy (albeit, only the needy within the Israel of God, as those who know how to rightly divide should be aware, since the Psalms — like the rest of the books of the Bible not written by Paul — weren’t to or about Gentiles, although that’s a whole other topic).

2) This cry for help then being followed up by the words of the Lord, where He promises to both protect needy people, and also to punish the wicked men who are troubling them. And finally…

3) The psalm is wrapped up by the psalmist acknowledging God’s promise, taking comfort in the fact that the words God spoke there are pure words, and hence that this promise can be trusted, which means he knows that the wicked men he was writing about will not remain exalted permanently as they would if God’s words couldn’t be trusted, and hence that the needy will indeed be preserved by God.

Scripture itself — particularly Scripture in written form — is obviously not the main focus, and hence not the context, of this psalm, and when we consider the context of God promising to deal with those who are harming the needy throughout the rest of the psalm, there’s literally zero reason to assume that the psalmist suddenly began discussing an entirely different topic (scriptural preservation in written form) that hadn’t even been hinted at anywhere in this psalm about saving the needy from the wicked prior to verse 6. And so, to insist that verses 6 and 7 are suddenly talking about a whole other topic altogether from the rest of the chapter, with verse 8 then returning to the original topic (even though that verse makes no sense standing on its own the way it would be without verses 6 and 7 being the connective tissue of God’s promise to preserve the needy and punish the wicked rather than being a random interjection about God promising to preserve Scripture in written form), rather than these verses telling us that God will preserve the needy as He promised in His words which preceded those two verses, just makes no sense whatsoever, and anyone who insists it does is obviously trying to shoehorn their desired meaning into the two verses (this is known as eisegesis) rather than interpreting these two verses based on the context of the rest of the chapter (which is known as exegesis).

To make this even more clear, if we did interpret it the way most KJV-Onlylists do, that would mean the psalm was actually written in four parts rather than just three:

Part 1 (verses 1-2), the words of the Psalmist: Help, Lord; for the godly man ceaseth; for the faithful fail from among the children of men. They speak vanity every one with his neighbour: with flattering lips and with a double heart do they speak.

Part 2 (verses 3-5), the words of the Lord: The Lord shall cut off all flattering lips, and the tongue that speaketh proud things: Who have said, With our tongue will we prevail; our lips are our own: who is lord over us? For the oppression of the poor, for the sighing of the needy, now will I arise, saith the Lord; I will set him in safety from him that puffeth at him.

Part 3 (verses 6-7), the words of the Psalmist: The words of the Lord are pure words: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt keep them, O Lord, thou shalt preserve them from this generation for ever.

Part 4 (verse 8), follow-up words of the Psalmist: The wicked walk on every side, when the vilest men are exalted.

If this were what the psalm was really getting at, it would also mean we’d have to break it down this way instead:

1) The psalm beginning as a cry for help to God by the psalmist because of wicked men oppressing the needy.

2) This cry for help then being followed up by the words of the Lord, where He promises to both protect needy people, and also to punish the wicked men who are troubling them.

3) The psalmist suddenly arbitrarily talking about how God will preserve His words in written form, having nothing to do with the parts of the psalm that came before or after this supposed interjection. And finally…

4) The psalmist returning to talking about the wicked men he’d previously been talking about in the psalm being exalted and walking on every side, for some reason, ending on a down note rather than acknowledging the promise made by God in part 2 to protect the needy.

When you look at it that way, I trust you can see which of those two breakdowns make the most sense, and that this psalm has nothing to do with scriptural preservation in written form at all.

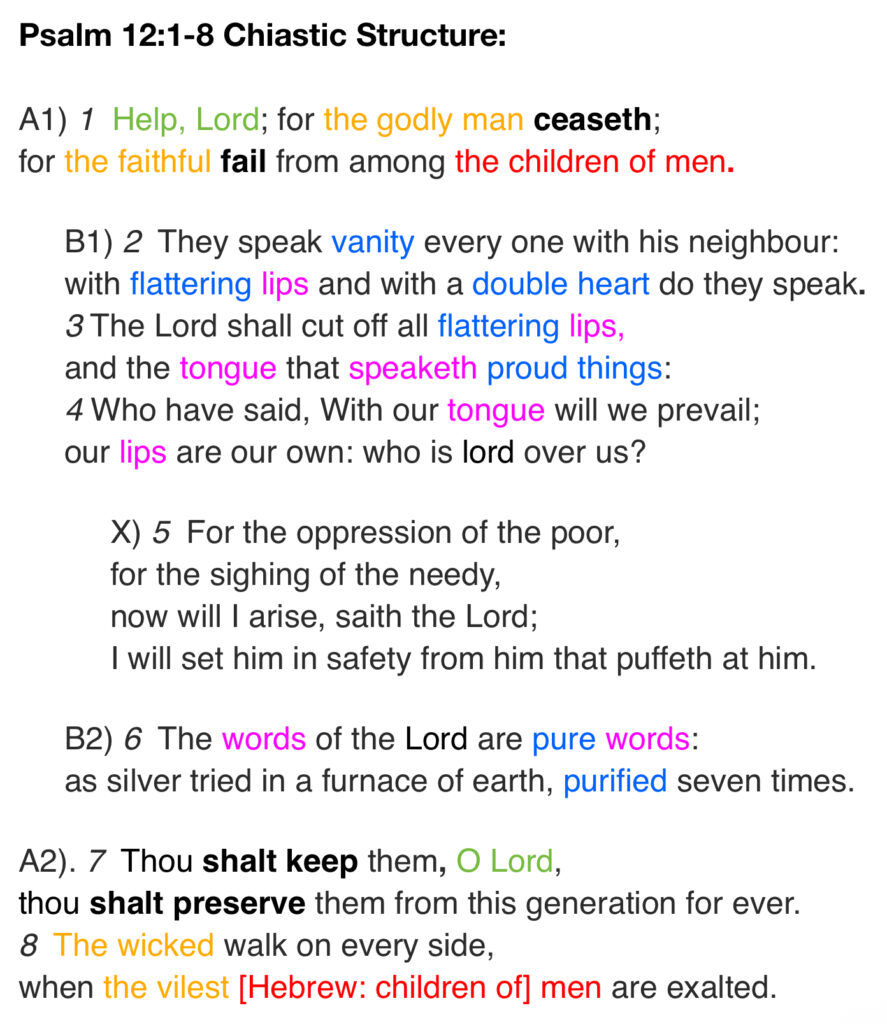

Of course, there’s also a second factor that most people aren’t aware of when reading this psalm, and this is its chiastic structure:

As you can see from that breakdown, the words of the Lord referred to in verse 6 are a chiastic, reverse reflection of the words of the ungodly in verses 2 to 4 (telling us that His promises are pure and can be trusted, unlike the vain words coming from the lips of the wicked), and you can also see from the breakdown that verse 7 (combined with verse 8) is a chiastic, reverse reflection of verse 1 (and not of verses 2 to 4, as it would have to be in order to be talking about words rather than people), revealing yet again that verses 6 and 7 have nothing to do with scriptural preservation in written form at all, but are rather talking about the preservation of the needy as promised by the words of the Lord. Of course, that’s not to say that His words in written form won’t be preserved in some way (whether completely or not, and whether this is done through the KJV or not), but by now it should be clear that this isn’t what those two verses in Psalm 12 are talking about (and this isn’t even considering the Hebrew grammar of the passage itself, which also proves that those two verses don’t mean what most KJV-Onlyists assume they do, although I’m going to leave that fact for others to demonstrate).

Now don’t get me wrong here. Defending the King James Bible is obviously a worthy cause, but we can’t do so by misinterpreting it. We have to be honest, both with the text and with our arguments, and so I’m calling on all King James Bible Believers to stop using this passage to try to defend God’s preservation of Scripture in written form, since it just isn’t saying what so many have assumed it is, and because you aren’t going to convince anybody who does know what this passage is actually talking about by using it to defend scriptural preservation anyway (instead, at best all you’re going to do by using this passage to defend the doctrine is convince them that you don’t understand hermeneutics or what this passage means, and at worst you’re going to convince them that you’re deceptive, and I trust that neither of those conclusions is what you want to convince them of).